By Seolha Lee

Segregation in cities has led to disinvestment and inequality in education, public health, and other opportunities, and a potential lack of social mixing across the city. However, residential segregation is only one part of segregation in a city. The location of jobs and third places (i.e. points of interest (POI)) may also perpetuate a lack of mixing among populations of different races, ethnicities and income groups. Analysis of individuals’ activity spaces shows that segregation is not just residential, but that activity spaces are segregated as well (Farber et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2018). Furthermore, segregation of activity spaces can be more intense than expected by residential geographic segregation (Dong et al., 2020), and perhaps explained by residents forgoing nearby POIs for more socially and culturally-attractive POIs (Arentze & Timmermans, 2008; Etminani-Ghasrodashti & Ardeshiri, 2015).

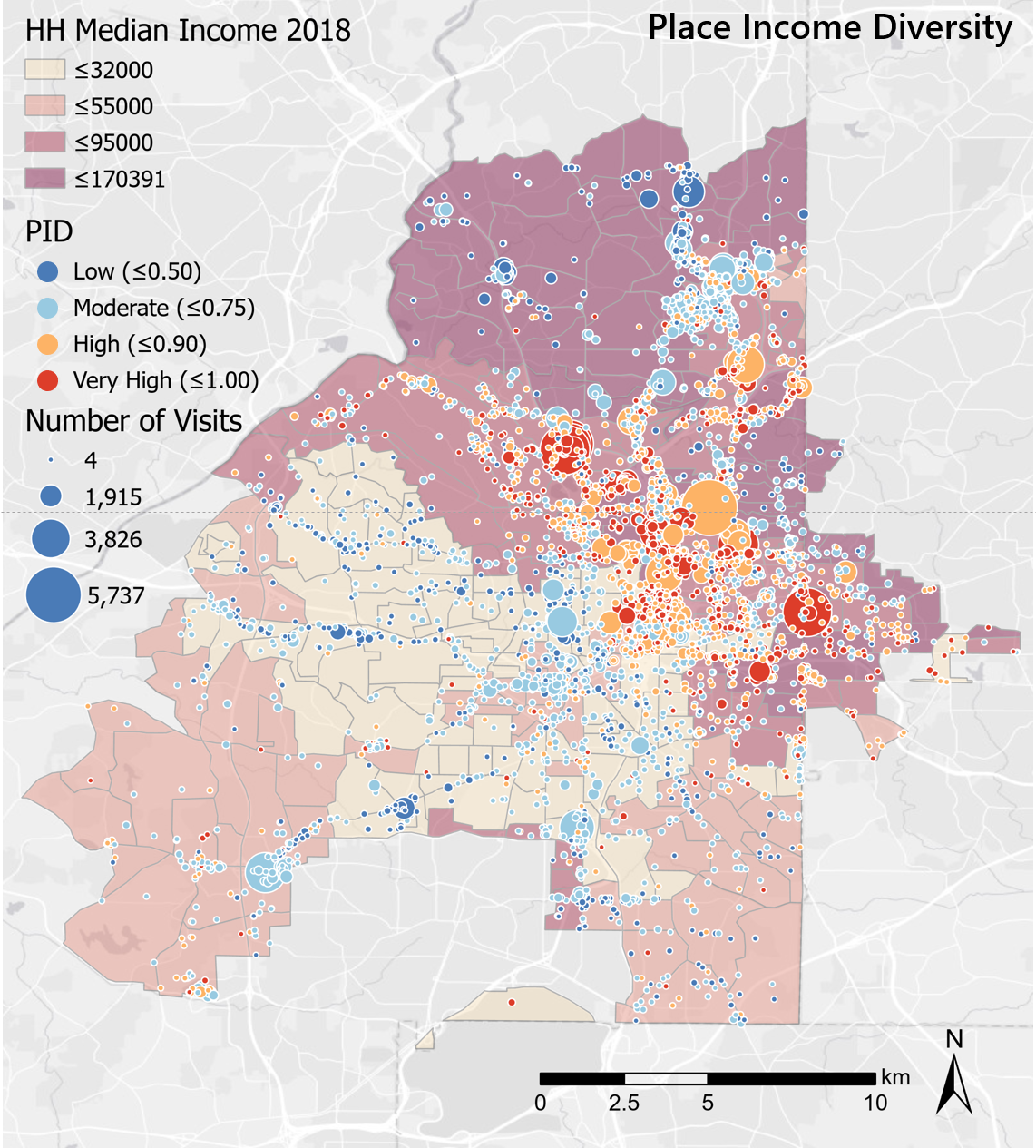

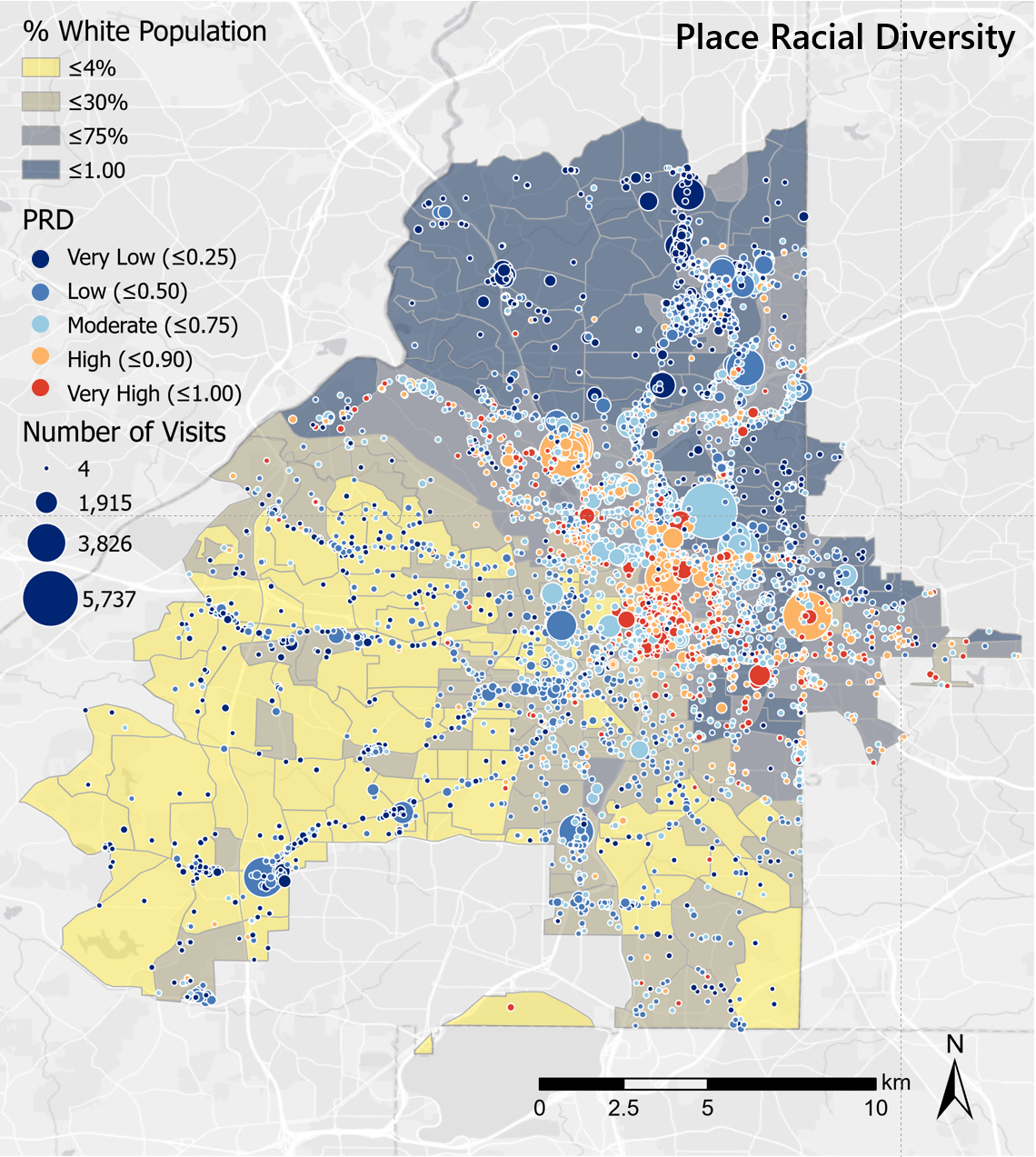

In this research, we ask which kinds of POIs (by neighborhood location and by category) have a more diverse set of visitors, defined as the proportion and number of visitors from neighborhoods of varying racial compositions and median annual income composition. We use 4,952 POIs within the city limits of Atlanta, Georgia as destinations. POIs are categorized as food outlets, retail, health/care services, personal services, or recreation. For each POI, we record the number of trips that originated in block groups of certain racial compositions and income compositions (from U.S. census data at the block group level) from March to June 2019. Trip data is provided by Safegraph at the block group-to-point level, and all trips are within the city of Atlanta.

We find that POIs in the downtown area, in nearby Midtown, and in adjacent gentrifying neighborhoods have a more diverse set of POI visitors. Our results also show that food outlets (restaurants, bakeries, bars, cafes, etc.) had the most diverse visitor populations in terms of both race and income. Additionally, many food outlets and recreation destinations had more frequent visitors from majority-white neighborhoods. Healthcare and retail POIs (supermarkets and other goods retail shops) attracted visitors from more homogeneous neighborhoods. The result was similar regarding income level. Lastly, residents in majority-Black or lower-income neighborhoods frequently visited places in an opposite socio-demographic setting of their own neighborhood, while residents in majority-white or higher-income neighborhoods did so less frequently.

We note limitations regarding potential ecological fallacy issues; that trajectories could represent workers and not patrons; and that the data may not capture most travelers or have spatial errors. Nevertheless, this research supports efforts to understand how POIs serve as potential mixing areas in the city and to serve urban residents more equitably with amenities and services. Urban planners seeking to facilitate connections across communities may be interested in how POIs may play a role in fostering new and existing social relationships and equitable services. In the future, we hope to perform similar analyses across multiple cities, and with more racial and ethnic groups, to find commonalities among locations that equitably attract visitors from across the community.